CINCINNATI - The Cincinnati Bengals enjoyed their most lopsided win of the season when they beat the Philadelphia Eagles at Paul Brown Stadium on Dec. 4, 2016.

Four days later, a Cincinnati health inspector threw a penalty flag in one of stadium’s 11 pizza stands.

“Countertops were filthy with food debris and beverage spills,” the inspector wrote.

It’s one of 33 violations documented in city records on Dec. 8 and one of 115 recorded at the Bengals' home field in 2016.

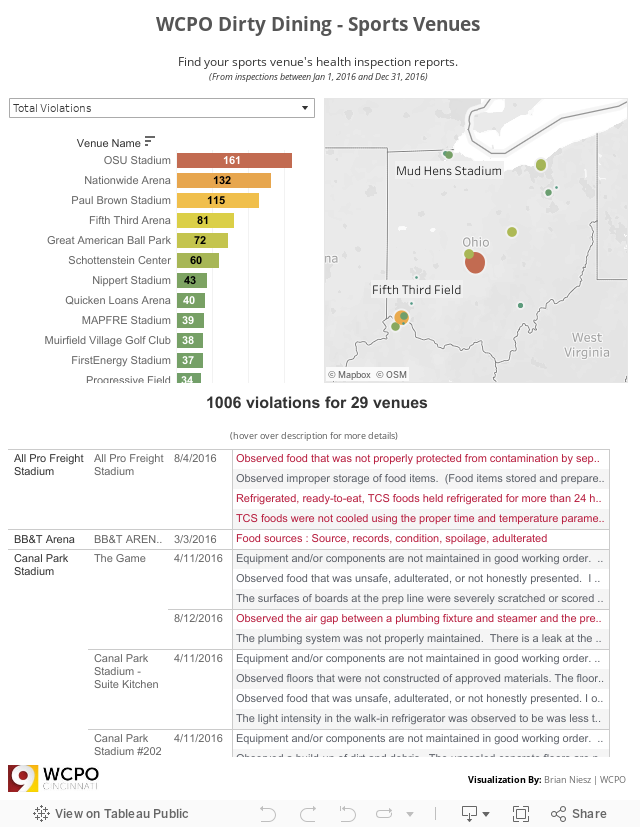

Paul Brown Stadium ranked third worst in a WCPO analysis of 29 sports venues in Ohio and Northern Kentucky, based on food-safety violations obtained from 12 health department jurisdictions. The home of the Ohio State Buckeyes was the worst, with 161 violations, followed by Nationwide Arena’s 133 infractions.

Fewer than 25 percent of the total violations involved critical matters such as hand-washing problems and food temperatures that permit the growth of bacteria. There were no citations documenting the presence of rodents, roaches and other pests. But there are lots of citations for cleaning and maintenance issues that can draw pests, including those “filthy” countertops at Paul Brown Stadium.

The Bengals referred questions to Aramark, its Philadelphia-based food vendor, which declined to interviewed, but said “issues raised in past reports were immediately addressed.”

OSU Stadium in Columbus

Ohio State referred questions to Levy, which oversees more than 100 food and beverage locations at OSU Stadium.

"On every event day we have several inspectors from Columbus Public Health on site,” Molly Kurth, Levy's vice president for hospitality and strategy, wrote in a prepared statement. “We proactively contract with a third-party sanitation expert, Everclean, to further monitor our operation and the training of our team members. Additionally, Everclean conducts full location audits annually, and (pest-control contractor) Orkin is on-site for monthly inspections."

Bigger venues tend to draw more violations, experts told WCPO. Some stadiums and arenas attract fans by the thousands on game day and serve up food at dozens of locations, all separately licensed and subject to multiple inspections per year.

“It’s not necessarily rocket science, but there’s a lot of moving parts that you have to take care of,” said Patrick Hannan, resident district manager for Chartwells, a Compass Group company that runs the food-service operation at Northern Kentucky University’s BB&T Arena.

“We usually have at least 30-35 associates behind this stand,” Hannan said on a tour of the arena. “We have three additional stands of this size around the concourse. In addition to that, we have suites, private catering, a bar downstairs.”

There is additional complexity with part-time nature of sports venues, where the kitchens can be dormant for months at a time – coming to life on game days with entry-level employees and volunteers who might not know state code sections for when to don a plastic glove and where they can store their personal drinks.

“We have to run food and food-handling at a very high level,” Hannan said. “You talk to people about what they do in their home kitchens. I can probably walk into your kitchen and home and you probably have a couple of critical (violations) there. And people don’t realize that.”

The Cintas Center at Xavier University had “insufficient sanitizer” in the “wiping cloth buckets” at three different concession stands in November. Inspectors forced the Bearcat Club at Fifth Third Arena to discard an “unlabeled chemical spray bottle” in December. How many home chefs toss out the Windex if the label falls off? How many know a sanitizer is sufficient if consists of one part bleach to nine parts water?

On the other hand, some violations are more obvious to the layman.

“Observed ear buds on the spatula for frosting,” inspectors wrote in a January, 2016 visit to Tim Horton’s stand at Nationwide Arena in Columbus.

Food fare at Great American Ball Park

“Observed a dish machine being ran without detergent,” inspectors noted at Great American Ball Park last August. “Ensure machines are properly stocked prior to operation.”

The food-service vendor for the Cincinnati Reds and Columbus Blue Jackets, Delaware North Sportservice, declined an interview but released a statement saying it provides staff with “continuous training” on food safety.

“Sportservice feeds an average of over 20,000 fans per game and as many as 42,000 at Great American Ball Park,” wrote spokeswoman Victoria Huong. “Hundreds of our employees work in several kitchens, dozens of concession stands, restaurants and clubs, and portable food and beverage carts. It is the equivalent of dozens of individual restaurants.”

Sportservice also feeds an average of 14,000 fans per game at Nationwide Arena – the Columbus home of the NHL Blue Jackets - and 1.5 million per year at Progressive Field, home of the Cleveland Indians. The company corrects critical violations on the day they are cited and reviews all inspection reports to “eliminate or reduce future concerns,” Huong wrote.

Even smaller sports venues have plenty of challenges.

UC Health Stadium, the home of the minor-league Florence Freedom baseball team, always had positive food-inspection scores until one conducted late last season that resulted in a score of 70 out of 100.

The team's staff corrected a number of the violations immediately, and the stadium got a score of 86 on an immediate follow-up inspection that same day.

"We completely shut down in the fall and completely reopen in the spring. We can get dinged on leaks in the faucet that we don't even know about until we turn it on for the first time," said Josh Anderson, the Florence Freedom's vice president and general manager. "There's nothing like food that's on the floor that's been picked up and put in a hamburger bun or things like that. We've never had an issue with things that have spoiled."

Even so, the team took its lower-than-usual scores from last year quite seriously, Anderson said, adding that he personally has become more closely involved in food operations to ensure they meet the team's high standards.

"I've involved myself a lot more," he said. "We were basically on cruise control with our inspections until the end of last year." But a 70 score “kind of gets your attention."

On the other end of the violation spectrum, the home of the Western & Southern Open had only one violation 2016: Not properly advising people in the ATP Dining Room of “the risk of consuming … raw fish for sushi.”

Part of the reason for the low violation count could be that the Lindner Family Tennis Center basically rebuilds its food service operation from scratch each year for the tennis tournament, said Dick Clark, the tournament's director of facilities.

The event's food court is comprised of 14 local restaurants. The restaurants have a cooking shelter on a concrete slab where staff prepares the food. The food is then assembled and sold in a separate tent that backs up to the cooking shelter, Clark said.

"I think the key is choosing quality partners," Clark said. "We put a quality product on the tennis court. So in everything we do, we look to mirror that same image from the music to the landscaping to the cleanliness of the bathrooms and even to the partners that we use for the restaurants and our catering."

The staff also has a meeting each year before the tournament that includes the restaurants and beverage vendor Coca-Cola, along with the health inspector. The goal of the meeting is to discuss procedures and expectations, Clark said.

"Luckily, we've chosen partners that have stayed with us for a long time and that have really, truly enjoyed the event," he said. "We're in it for the long haul so we want people that are just like us and are very proud of what they do."

Buffet stand at Paul Brown Stadium

In some respects, though, sports facilities should have an easier time with food inspections than a lot of restaurants, said O. Peter Snyder, president of Snyder HACCP, a food-safety consulting firm near St. Paul, Minnesota.

"Normally the food that they sell has enough preservatives in it that you don't have any issues. I'm thinking particularly of all the sausages of various kinds," Snyder said. "You can let the stuff sit out for hours, and nothing's going to grow. Yes, a hamburger out for enough hours might cause a problem. But hotdogs and so forth, they've all got nitrates in them that make it almost impossible for them to fail."

The bigger problem, Snyder said, is hand washing.

"The bathrooms are crowded, and people don't wash their hands, and that's how salmonella and viruses get transmitted," Snyder said.

No matter the venue, Snyder said the basics of food safety remain the same:

"Hot food hot and cold food cold, and wash your hands," he said. "And if we do that, we don't have to worry about bar towels and wiping things up."